Fanny Mendelssohn: A Study in Contrasts

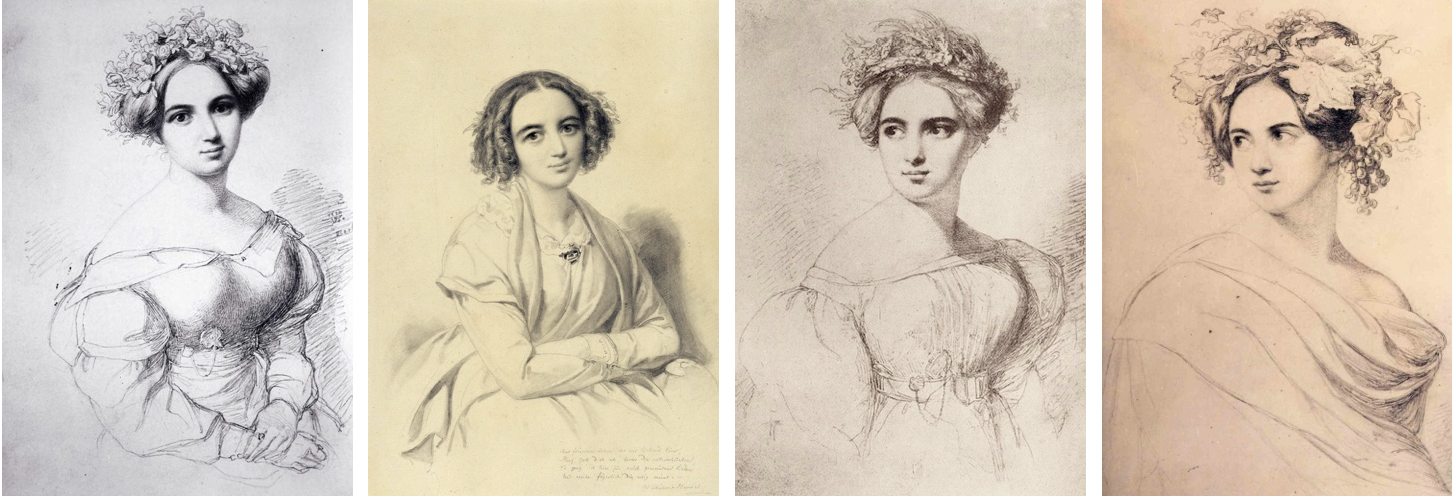

Sketches of Fanny Mendelssohn, all attributed to her husband, Wilhelm Hensel

We read a great deal about Fanny Mendelssohn the composer, but I must confess I also had a great interest in just who she was as a person as well, which led me to do a certain amount of research. What I discovered is that behind the façade of a woman anxious to both please and conform based on the societal norms of the time, was someone who was not without a great number of strong opinions, and a formidable presence in her own right.

The interview with Sheila Hayman, Fanny’s great-great-great granddaughter, by Jessica Duchen, perhaps provides some of the greatest insights, which I found fascinating. Hayman describes a woman with a very strong personality:

[S]omebody completely incapable of disguising her feelings. If she liked people, she loved them; if she didn't like them, you saw it all over her face. She hated parties, formal gatherings of any kind, paying calls, giving cards and wearing hats because the veils got caught in her glasses. And she couldn't see the point of jewelry.

She follows this up with a description of yet another encounter:

Fanny comes across as affectionate, clever, sharp-witted and sometimes scary. ‘Everybody was frightened of her,’ Hayman says. The composer William Sterndale Bennett was a case in point: ‘He said that he had played for Felix often, but that having to play for Mrs. Hensel, and to think that this formidable person should be a woman, was absolutely terrifying.’

In terms of her role as a wife and mother Hayman goes on to observe:

Fanny wanted to be a good wife, mother, sister and housekeeper, to do all the things that the family and society expected her to do. I think she found it difficult to achieve that balance. She struggled with it all her life.

Looking at these descriptions however alongside the ways in which she kept her work as a composer virtually hidden, it seems somehow hard to imagine her capable of having such strong opinions on other fronts.

We discover from Hayman and Duchen for example:

She wrote Das Jahr, but didn’t publish it, and mentioned it only in one letter. That’s what’s so extraordinary: she writes an absolutely barnstorming piece of music, yet refers to it in a casual way as a little bit of fun with which she’s been amusing herself and that might perhaps entertain other people.

Yet, again according to Hayman, she held very clear ideas about other composers, and showed no real interest in the works of anyone save her brother, despite having met some of the most important musicians of the day including Paganini, Chopin and Berlioz!

Although her husband, Wilhelm Hensel, would always prove very supportive, his enthusiasm for her work could only go so far as he was a great painter, but not a musician.

Her greatest encouragement however would come from French composer Charles Gounod, and led to the composition of one her most celebrated works, Das Jahr. Having met him in Rome in 1839, he said to her “Your creativity blossoms when you feel confident in what you’re doing and other people are confident in it as well.” According to Hayman:

Gounod was in residence at the Academie Française. She decided that she could really respect him – and he was absolutely blown away by her. It seems that German music was not familiar in Italy at that point, or in France. According to what I’ve been told, Fanny brought Beethoven and Bach to Rome. She sat down and played five Beethoven sonatas in a row, to show Gounod what he’d been missing. Therefore she was admired and esteemed as much for the musical knowledge and tradition that she brought with her as for her own extraordinary gifts.

One has every reason to believe that Fanny was indeed greatly encouraged by Gounod’s enthusiasm as she wrote: “I was never made so much of in my life, and it’s really rather pleasant!”

Whether or not his encouragement was enough to cause Fanny to shed some of her doubts and misgivings about her own work is something we can never know. However, it is clear that with more than 400 compositions to her credit, we as listeners are all the better for her continuing to work so abundantly and so diligently over the relatively short period her forty-one year life, all while leaving behind a legacy of truly great music.

Tap an icon below to share this blog on social media, email, or your favorite messaging app.